Database Indexing

How Database Indexes Work

Physical Storage and Access Pattern

- Data lives on disk (typically SSDs nowadays), we can only process it when it's in memory.

The Cost of Indexing

- Every index we create requires additional disk space.

- When we insert a new row or update an existing row, we need to update the index.

- With multiple indexes, we need to update all indexes.

- Some classic case:

- Logging table

- Frequent writes but infrequent reads

- We constantly inserting new records but rarely querying old ones.

- Small tables with just few hundred rows

- The cost of maintaining an index and traversing its structure might exceed the cost of a simple sequential scan.

- Logging table

Pros and Cons of Indexing

Pros: Improve Query Performance

- If a query does not use an index, it will result in a full table scan, with a time complexity of

O(n). - However, if an index is used, the query can levearge a binary search algorithm to quickly locate the target data.

- The time complexity is

O(log_d n), where d is the maximum number of childs allowed for a node.

Cons:

- Indexes require physical storage space, and the more indexes there are, the more space they consume.

- Creating and maintaining indexes takes time, and this time increases as the data volume grows.

- Indexes slow down insert, delete, and update operations on the table. This is because the B-tree, used by the index, must be dynamically rotated to preserve its ordered structure each time the data is modified.

Index Types

B-Tree Indexes

- Fast searches and updates.

- Acheived by maintaining a balanced tree structure that minimizes the number of disk reads required to find a record.

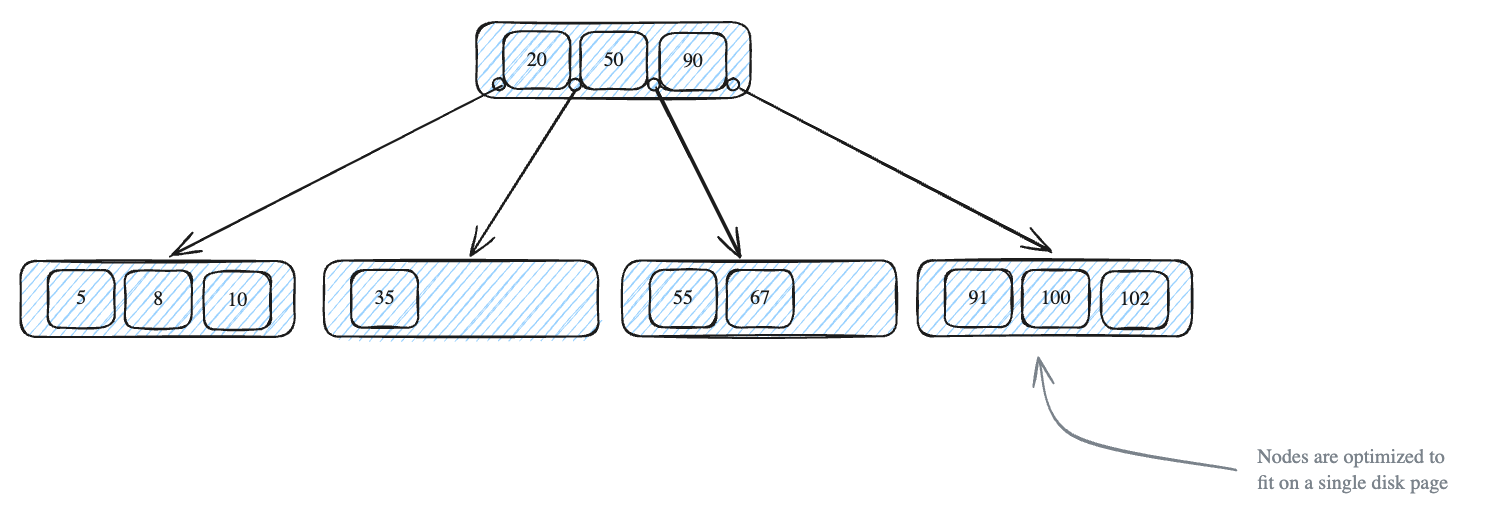

Structure of B-Trees

- A B-Tree is a self-balancing tree that maintain sorted data and allows for efficient insertions, deletions, and searches.

- B-tree nodes can have multiple children - typlically hundreds in practice.

- Each node contains an ordered array of keys and pointes.

-

Every node in a B-tree follows strict rules:

- All leaf nodes must be at the same level (depth).

- A node with k keys must have exactly k+1 children.

- Keys within a node are kept in sorted order.

-

This structure maps perfectly to how databases store data on disk.

-

Each node is sized to fit in a single disk page (typically 8KB), maximizing our I/O efficiency.

Real-World Example

- PostgreSQL uses B-trees for primary keys, unique constraints, and most regular indexes.

CREATE TABLE users (

id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

email VARCHAR(255) UNIQUE

);

Why B-Trees Are the Default Choice

- Mintain sorted order, making range queries and ORDER BY operations efficient.

- Self-balancing, ensuring predictable performance even as data grows.

- Minimize disk I/O by matching their structure to how databases store data.

- Handle both equality searches (email = 'x') and range searches (age > 25) equally well.

- Remain balanced even with random inserts and deletes, avoiding the performance cliffs you might see with simpler tree structures.

Inverted Indexes

-

B-tree excels at finding exact matches and ranges, they fall short when we need to search through text content.

-

Why Index using B-tree not works?

SELECT * FROM posts WHERE content LIKE '%database%';- Even with a B-tree index on the content column, the database can't use the index at all.

- B-tree indexes can only help with prefix matches (like 'database%') or suffix matches (if you index the reversed content).

- When the pattern could match anywhere within the text, the database has no choice but to check every row.

-

How Inverted Indexes works?

- Think of it like the index at the back of a textbook.

doc1: "B-trees are fast and reliable"

doc2: "Hash tables are fast but limited"

doc3: "B-trees handle range queries well"

-- create a mapping of

b-trees -> [doc1, doc3]

fast -> [doc1, doc2]

reliable -> [doc1]

hash -> [doc2]

tables -> [doc2]

limited -> [doc2]

handle -> [doc3]

range -> [doc3]

queries -> [doc3] -

Trade-offs:

- When a document changes, we need to update entries for every term it contains.

Index Optimization Patterns

Composite Indexes

-

Instead of creating separate indexes for each column, we create a single index that combines multiple columns in a specific order.

-

Consider we create two separate indexes:

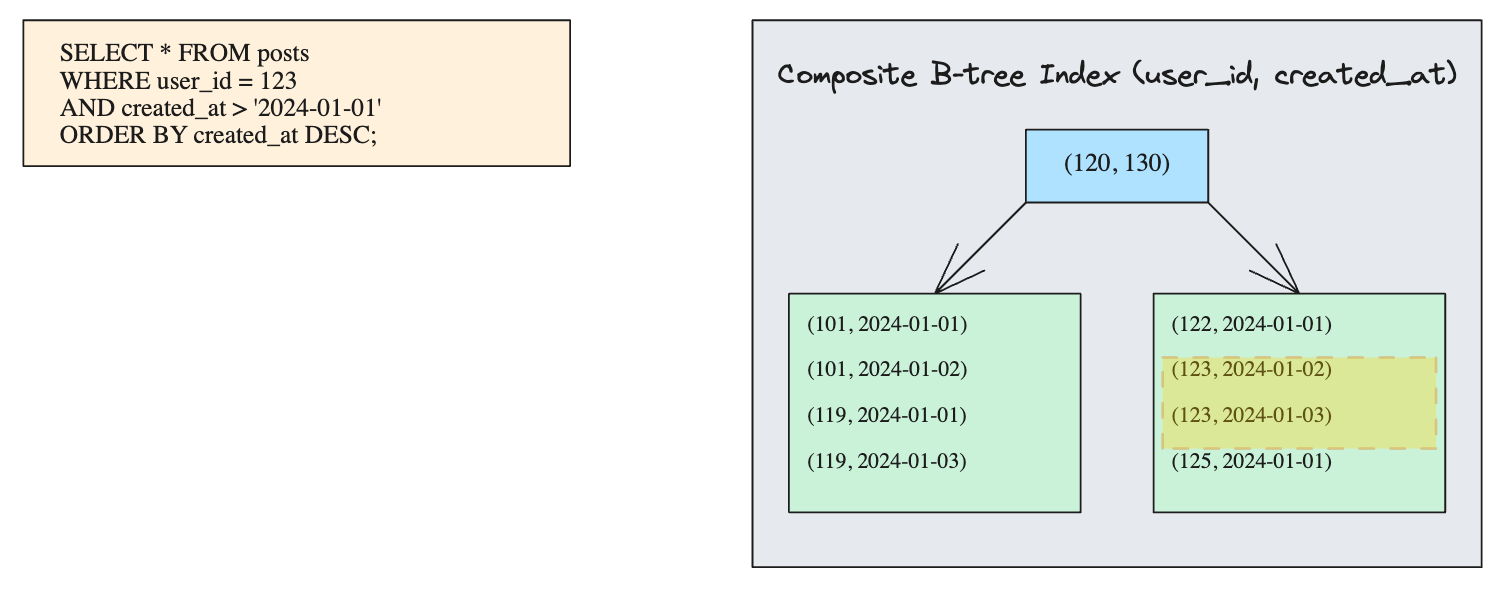

SELECT * FROM posts

WHERE user_id = 123

AND created_at > '2024-01-01'

ORDER BY created_at DESC;

CREATE INDEX idx_user ON posts(user_id);

CREATE INDEX idx_time ON posts(created_at);- But this isn't efficient. The database needs to:

- Use one index to find all the posts for user 123.

- Use another index to find all posits after 2024-01-01.

- Intersect these results.

- Sort the final results set by

created_at.

- But this isn't efficient. The database needs to:

-

When we use composite index,

CREATE INDEX idx_user_time ON posts(user_id, created_at);

- Each node's key in the B-tree is actually a tuple of the indexed columns.

- The keys are in sorted order based on

user_id, thencreated_at.Conceptual Ordering of Keys(1, 2024-01-01)

(1, 2024-01-02)

(1, 2024-01-03)

(2, 2024-01-01)

(2, 2024-01-02)

(3, 2024-01-01) - When we execute our query, the database can traverse the B-tree to find the first entry for

user_id=123, then scan sequentially through the index entries for that user. - Both filtering and sorting in the query are handled by a single index scan.

The Order Matters

-

Fields placed earlier in the index are more likely to be used for filtering.

-

Fields with high selectivity (or high cardinality) should be placed first, as they are more likely to be used by a wider range of SQL queries.

-

For example:

- A field like gender has low selectivity (e.g., only two values: male and female), making it unsuitable for indexing or for being placed early in a composite index.

- A field like UUID has high selectivity, making it ideal for indexing or being placed early in a composite index.

-

If an index has low selectivity and the values are evenly distributed, querying any value might return a large portion of the data (e.g., half the table).

Covering Indexes

- An index that contains all the columns required by a query, allowing the query to be completed without accessing the table's data rows.

- All the data needed for the query can be retrieved directly from the index.

- Improves query performance by reducing the number of data page accesses, thereby decreasing I/O operations.

CREATE TABLE employees (

id INT PRIMARY KEY,

name VARCHAR(100),

age INT,

department VARCHAR(100),

salary DECIMAL(10, 2)

);

CREATE INDEX idx_name_age_department ON employees(name, age, department);

SELECT name, age, department FROM employees WHERE name = 'John';

Situations Where Indexes Become Invalid

LIKE %xxorLIKE %xx%in LIKE Queries

- The index becomes invalid because the query cannot utilize the sorted structure of the index effectively.

- Using Functions on Indexed Columns in Query Conditions

SELECT * FROM users WHERE UPPER(username) = 'ALICE';

- Performing Expression Calculations on Indexed Columns

- If an indexed column is used in an expression (e.g.,

WHERE indexed_column + 1 = 5).

- Implicit Type Conversion Due to String-to-Number Comparison

- If the indexed column is a string and the query condition uses a numeric value (e.g.,

WHERE indexed_string_column = 123), an implicit type conversion occurs.

- Violating the Leftmost Matching Principle in Composite Indexes

- For composite indexes, queries must adhere to the leftmost matching principle, meaning the query must match the index fields in their defined order (left to right).

- Using OR with Mixed Indexed and Non-Indexed Columns

- In a

WHEREclause, if the condition before anORoperator uses an indexed column but the condition afterORuses a non-indexed column, the index becomes invalid.